Penelope Maddy’s Workbench

Philosophical Screenwriting, ‘Pity the Poor Reader’, & Bedtime Stories

A writer’s world is often invisible from the outside unless they let you in. Sometimes when a sentence, paragraph, or essay strikes you as forceful or elegant, you might try to reverse engineer the author’s process. You try to articulate rules or ideas that shaped the author’s choices. Later on, if you speak with the writer, you might be humbled upon finding out you had no real clue how they do their thing. That’s a lesson I learned when talking with Penelope Maddy about her craft.

Maddy’s work investigates foundational issues in the philosophy of mathematics, including questions about realism and naturalism, as well as methodology in science and philosophy and epistemological questions about skepticism.

Maddy completed her Ph.D. in philosophy at Princeton University in 1979 and her B.A. in mathematics from the University of California, Berkeley in 1972. Currently, Maddy is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of California, Irvine. Previously, she held positions in the philosophy department at the University of Illinois at Chicago and in both philosophy and mathematics departments at the University of Notre Dame. She is the founding chair of UC Irvine’s Department of Logic and Philosophy of Science. Her scholarship has been recognized by many awards and honours, including election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1998), the presidency of the Association for Symbolic Logic (2007–09), and the presidency of the American Philosophical Associate Pacific Division (2019–20). In 2014–15, she was chosen to deliver the Phi Beta Kappa/Romanell Lectures, a series of public talks “intended to recognize not only the distinguished achievement but also the recipient’s contribution or potential contribution to public understanding of philosophy.”

A decade ago, in June 2015, I met Maddy in person, immediately following one of her Romanell lectures. After our short conversation, I wrote her an email:

We talked briefly after your Romanell lecture yesterday. You asked me to send you Jonathan Schaffer’s paper on the “debasing demon”. Let me say that your lecture is written in a terrific style. It is elegant and engaging and accessible, but with enough close-up detail to keep specialists listening carefully. I admire your sensitivity to the fact that our philosophical problems depend on history and culture. I am eager to hear your lecture on Friday.

The next lecture didn’t disappoint, and I emailed Maddy again to comment on her distinctive approach to epistemology. In her reply, she remarked: “This is the first time anyone has ever called me an ‘epistemologist’!”

After reading the published version of her Romanell Lecturers, I wrote to her in 2023, asking if I could interview her. She was game, at first. But after a series of initial exchanges she expressed some uncertainty about why her approach to writing would interest me or anyone else. “I find this writing about writing oddly embarrassing,” she told me. At one point, I half suspected that she would bow out, but she put up with my questions and we enjoyed a conversation about many topics. Maddy writes graceful, fluid prose, and I was pleased to learn about the integrity, patience, and delight in art that drives her writing. I am glad to know something of the story of her development as a philosophical writer.

When I first met Maddy, I noticed that she rode a scooter, but I didn’t know the backstory. In 2012, at age 61, Maddy developed neurological condition that left her unable to walk any significant distance; more recently, it progressed to limit her ability to sit as well. When we talked about one of her inspirations, the writer Samuel Beckett, I wasn’t entirely sure what made Beckettian existentialism attractive to Maddy. Maybe an emblematic line from Beckett’s penultimate story, Worstward Ho, points in the right direction: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

When you were starting out in philosophy, did you have models for good writing?

My first exposure to philosophy was in an undergraduate philosophy of math course taught by Charles Chihara. He was trying out drafts from his Ontology and the Vicious Circle Principle, so he got a lot of push-back from us math majors. As far as writing goes, I admired Frege’s Foundations of Arithmetic for its refreshing directness, though I’ve subsequently come to wonder how much of that may be due to his translator, J. L. Austin. (I didn’t know anything about Austin at the time, hardly noticed the other name on the title page.) Then, of course, there was Quine in those bracing classic essays, “On What There Is” and “Two Dogmas”. Still, much as I admire his clever turns of phrase, I don’t aim for that sort of thing in my own writing. What I care about most is clarity, straightforwardness, and—here I admit to a stylistic preference—the natural rhythm of the sentences.

You’ve read broadly in both contemporary philosophy and history of philosophy. I’m guessing your exposure to new types of writing over the years shifted your own sense of what’s good writing.

What I most remember is the moment when I started to read the early moderns.

In graduate school, I was in a History and Philosophy of Science program that, ironically, didn’t require any history of philosophy. I’d read the standards as a duty, on my own and as a TA, not taking them much to heart (except for the Bishop Berkeley, whose work on vision and Newtonian physics I very much enjoyed reading as an undergraduate). The mathematics I wanted to philosophize about only arose in the late nineteenth century, so even the old musings on infinity didn’t have much bearing on my interests. In more recent years, I gradually came to realize that I couldn’t keep relying on Quinean naturalism as the methodological backdrop for my work in the philosophy of mathematics—the indistinct idea of naturalism in the back of my mind was really too far from his to keep pretending otherwise.

Starting from scratch, I hit on the idea of using radical skepticism as a diagnostic instrument: naturalism, I figured, is a position that somehow rejects or side-steps the skeptical challenge; how does this go? To answer that question, I thought I should return to the sources, which led me to Descartes, then Locke and Berkeley, Hume, and finally, to the delightful Thomas Reid. After years of reading contemporary analytic epistemology, I was stunned to find these authors addressing the central question—how do we gain reliable information about the world?—baldly, frankly, free of the centuries of clever philosophical accretions and distortions. I was transfixed. The story of my infatuation with the early moderns—and what I take to be the morals—are contained in the essay “A Plea for Natural Philosophy”.

Soon thereafter came Moore and Austin’s bold writings on these same topics: “Here’s a hand”, for goodness’ sake, or “Enough is enough”. Among more recent philosophers, I especially admire Barry Stroud’s jargon-free writing and Janet Broughton’s elegant little book on Descartes.

Just a moment ago, you mentioned the “natural rhythm of the sentences”. How would you describe the rhythm of the sentences you aim to write? How do you know which sentences need refinement because they’re not, well, natural enough?

I’m not sure I can say anything particularly helpful about ‘rhythm’. My only real test is to read the sentence out loud. It doesn’t have to be short, but the clauses have to be parallel, and you should never have to refer back to earlier parts to understand what’s going on in later parts. So I guess that is my method: read the sentence out loud; see if it flows; if it doesn’t, fix it.

Do you have any specific speaking voice that you use when testing your prose? I mean, are you reading to a particular audience, or just to yourself?

I just read the sentences and paragraphs to myself and edit to suit my own ear, though I do sometimes adjust somewhat depending on the proportion of mathematicians to philosophers in the intended audience. But I do think seriously about audience when I’m figuring out where to pitch the whole piece of writing—how much background of what sort am I going to presuppose? Often I’ll picture one or two specific people to keep my eye on the target.

As it happens, I was trying to work up to a book on skepticism when the invitation came to deliver the Romanell lectures. The opportunity to pitch that material to a semi-popular audience reoriented the project in a way that suddenly felt right, even fun.

The published version of your Romanell lectures—What Do Philosophers Do? Skepticism and the Practice of Philosophy—is indeed fun and highly readable, too. But back to rhythm for a moment: are there any non-academic writers you’ve been drawn to who make sentences with a desirable rhythm?

Oh, yes! I started thinking about sentences late in college, I suppose as I was beginning to move away from mathematics, toward I wasn’t sure what, but it was going to involve writing. On my own, in a flurry, I romped through the Great Writers of the Past, buying up clumps of cheap used copies from Moe’s in Berkeley. When I got to Proust—Montcrieff’s translation in those days—I was amazed at how he could keep a single sentence going for so long without losing the reader. I pushed myself to write page after page of meandering journal entries, figuring I had to get out a lot of bad sentences before I’d be able to write any good ones.

Speaking of fine sentences, Cheever and Updike are a couple of examples that occur to me. When I read a paragraph of Cheever out loud, I’m in awe. How does he do that?! Heck, when I read a paragraph of Cheever out loud, I’m tempted to think he’s my favorite writer of all time.

Aside from reading aloud, are there other methods you often use while writing?

Another maxim for me is: Pity the Poor Reader. In philosophy especially, I figure the reader is nearly always gasping for breath, in danger of being swept out to sea, so the writer should do everything in their power to help. Keep things as simple and explicit, as direct and straightforward as you can. Don’t hedge or obfuscate. Don’t use jargon unless you define it. (Philosophical words—realism, analyticity, empiricism, etc.—are used in so many different ways that it’s not safe to call on one without saying explicitly what you mean by it.) Give concrete examples.

I have a weakness for historical delights. One of my students used to refer to my “history of science and mathematics bedtime stories”.

Excellent advice. Let me ask you about the historical “bedtime stories”. I think I know what your student was talking about. Just one example from your writings:

The theory of vision drew Kepler’s attention after a solar eclipse in 1600: he noticed that during the eclipse, the diameter of the moon measured incorrectly through a pinhole camera; he was led to develop a theory of the radiation of light through a small aperture that explained the phenomenon; he then realized that all astronomical observations were affected not only by the optics of small apertures in the instruments but also by the optics of vision itself, which also takes place, after all, through a small aperture.1

The Kepler story sparkles. Where do you find bedtime stories and what are the features of good ones?

Some passages in history are delightful, aren’t they? Just reading around, they jump out. Sometimes I pack them into long footnotes and then reluctantly delete them if I’m in danger of violating a firm word count.

In general, I like to give other authors their due, in their own words. I tell my students: if you’re going to claim a person thinks such-and-such, give me a quotation where you think they say such-and-such, so I can judge for myself.

Show the receipts!

The advice comes from hard experience. As clearly as I try to express myself, my own views are misrepresented more often than not. Allow the author their own voice. Besides, what other writers write is often plain delightful. I like to share.

What you say reminded me of a passage from the American novelist and essayist Marilynne Robinson. I’ll quote the passage in full so you can, well, judge for yourself:

I often look at primary texts, books generally acknowledged to have had formative impact, because they are a standard against which other things can be judged, for example the reputations of these same works, or the reputations of those who wrote them, or the cultures that produced and received them, or the commentaries and histories which imply that their own writers and readers have a meaningful familiarity with them. If the primary text itself departs too far from the character common wisdom and specialist wisdom (these are typically indistinguishable) have ascribed to it, then clearly some rethinking is in order.2

One of Robinson’s complaints about intellectual and academic culture is that people don’t bother to read primary texts—they get by on the common wisdom, which can be limited or misguided.

Interesting that you should mention Robinson: Gilead is a beautiful book—John Ames is a great character. Anyway, if I understand what she’s up to in the passage you just quoted, I guess I agree. It seems to me that people like the Good Bishop Berkeley or Thomas Reid or G. E. Moore or J. L. Austin are all much more interesting than the general understanding. It has been immensely rewarding to try to think my way into their turns of mind.

Sharp little details from history add colour and sometimes charm the reader. Years ago, an academic historian friend of mine read a draft I was working on and sort of balked at a fanciful example I’d made up. I wish I could dredge up the draft now and see his comment, but it was some sci-fi philosophy example—maybe something involving superscientists or an evil demon or whatever. My friend noted that the fanciful example would distract a non-philosophy reader. Couldn’t I find a structurally equivalent example to do the same job, but one better grounded in reality? I’ve been trying to do that ever since.

Down to earth examples are always best, I think. (See Pity the Poor Reader.) More philosophically, I sometimes said to my students, I don’t care what happens on Mars (Twin Earth, etc.), tell me what happens here!

Just a story… if you’ve read Austin’s writings on skepticism you’ll remember that many of his examples are drawn from his apparently intimate knowledge of small British songbirds. (I think goldfinches have made their way into the epistemological literature, along with ‘medium-sized dry goods’.) When I was writing the little skepticism book, I thought to follow his example, not by talking about birds, but by drawing on a bit of local color—why should the English countryside be more suitable than Southern California?—so I concocted an extended surfing example! Had to consult with my colleague Aaron James—a life-long dedicated surfer—to get the details right.

What sort of influences did you carry from childhood and high school to college? What sort of books did you enjoy reading when you were young?

In high school, I was on the math team. One of the events involved preparing a few five-minute lectures on assigned topics and gearing up to be questioned on them afterwards. The team sponsor, our math teacher, had a book cabinet at the back of her classroom, and one afternoon she opened it up and gave me free access to everything she’d squirreled away there. That’s how I first learned about the foundations of math and the continuum problem, topics I’m still writing about to this day.

I also remember reading Beckett and Kafka and T. S. Elliot and Hemingway in high school. An exciting time.

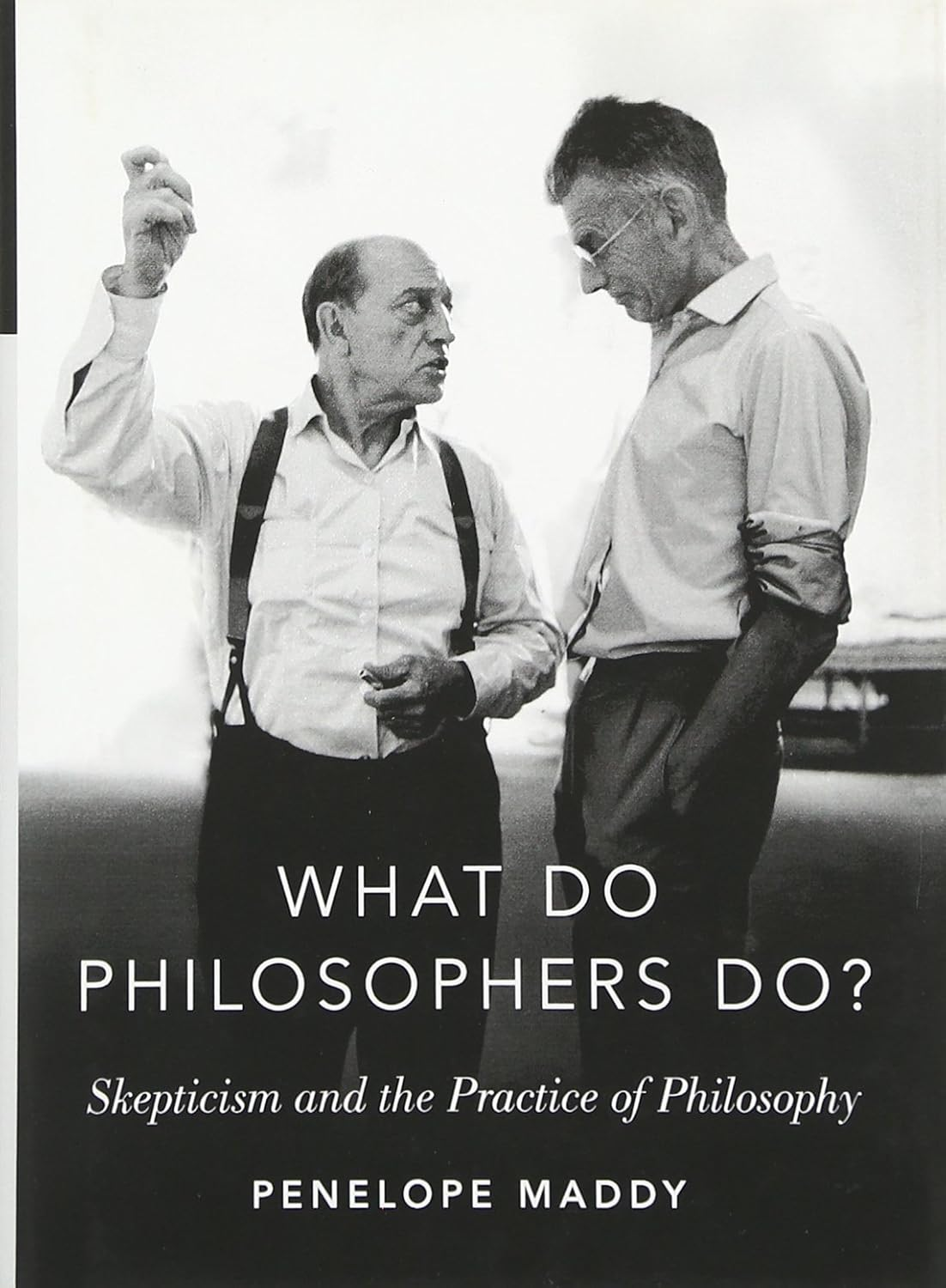

On the cover of What Do Philosophers Do?, there’s a striking picture of Beckett and Buster Keaton.

Beckett and Keaton have been two of my greatest heroes since college, when Keaton’s movies were being rediscovered and shown in Berkeley art houses. The fact of their having crossed paths is nearly too wonderful to be believed, and then the photographer, Steve Shapiro, perfectly captured this exchange of ideas. (Shapiro took some famous photos of the civil rights movement.) When Peter Ohlin at Oxford University Press asked what image I’d like to have on the cover of the skepticism book, I grabbed the chance of having this picture with me for the rest of my born days. It wasn’t easy to get the rights—a little education in itself—but it was well worth it.

A little earlier on, I mentioned one mantra of my young self: you have to get out a lot of bad sentences before you can write any good ones. I used to repeat that to my students. Now here’s how a real writer would put it: “until the gag is chewed fit to swallow or spit out the mouth must stutter or rest”. That’s the young Beckett, apologizing in a letter for being unable to say “what I imagine I want to say”. Just stumbled across it in the first volume of his collected letters.3

A vivid line from Beckett. I haven’t read much of his writing, but isn’t a theme in Waiting for Godot that communication is futile?

Well, for Beckett, pretty much everything is futile. Nevertheless, we go on.

I’ve read a bit about Beckett’s life—the guy sure didn’t have an easy time. In what ways do you think of him as a hero?

I think my favorite play of all time is Happy Days—you know, the one-hander with the woman buried up to her waist in act one and up to her neck in act two. She remains chipper, as best she can: “This will have been another happy day! After all. So far.” She’s my hero. Of course, Godot is great—“he blames on his boots the faults of his feet” and the bit about the two thieves, playing on the beautiful line, “Do not despair, one of the thieves was saved; do not presume, one of the thieves was damned” (Vladimir: “a reasonable percentage”). I’m also a great fan of Krapp’s Last Tape.

These days, I’m enjoying Joseph Conrad—such a sharp moral vision, he lets no one off the hook. I’ve been a Trollopean for decades. He treats his characters with such warm humanism. Also rereading Kafka, Cheever, Joyce (more ambivalent, less respectful this time around), Melville, Wharton…

A film critic once described Buster Keaton as “a man inclined towards a belief in nothing but mathematics and absurdity… like a number that has always been searching for the right equation.”4 It was only a matter of time before Keaton would wind up on the cover of a book about skepticism.

Very nice! Keaton’s schemes have an undeniable inner logic—you can watch the gears turning behind that beautiful face—it’s just that he’s trapped in the absurd universe. The pairing with Beckett on the book cover wasn’t accidental: Beckett puts vaudeville in existentialism—Keaton puts existentialism in vaudeville.

Did you ever want to write literature?

Back in college, when I felt myself drifting away from mathematics, I knew wherever I was going to end up would involve writing. I was reading the Greats, so I naturally wondered if I should be working toward fiction-writing of some kind. I was bad at it. Kept tripping over myself trying to sound ‘literary’ or something like that. No good. It wasn’t until much later, in the mid-80s, when I was homesick for California and thinking vaguely of a career change, that I took a shot at screenwriting. So much more congenial. There any literary conceit would be out of place, one of the cardinal sins is too much description (‘directing on the page’). All that really matters is good characters, believable dialogue, and a clear narrative arc. I wrote half a dozen feature-length screenplays during that period.

I wasn’t expecting that. But it isn’t so surprising to me, given the elegance and strong sense of control I find in your writing. What kept you in academic philosophy?

Various factors played into the decision to stay in philosophy, one being a completely unexpected offer of a job at UC Irvine. At the time, I was already in Southern California on extended leave—I grew up here and living anywhere else always felt a little like exile—so the opportunity to stay home changed the decision calculus considerably. But more to the point for our discussion here: when I wondered what to write about in my next screenplay, I had to scrounge around for something of interest, news clippings, etc., but when it came to the next philosophical topic, I found half a dozen that I was eager to work on already there clamoring for attention. This seemed significant.

It’s also true that after Naturalism in Mathematics—when I realized I had to face up to metaphilosophy, radical skepticism, and logical truth before returning to the traditional metaphysical and epistemological questions left open in that book—this opened up the field of philosophical writing in a way that finally drove out any thought of other kinds of writing.

Did you try to address any philosophical themes in the screenplays you wrote? And did anything happen with those screenplays or are they collecting dust in a file drawer?

I had a couple of agents, optioned one script, was offered a job punching up someone else’s script, but by then, I’d wandered back into academia with the job at Irvine.

To your question, there wasn’t much philosophy in my screenplays. For one of them, I wanted to describe a positive future in the midst of all the dystopian movies at the time (e.g. Blade Runner), also some sneaky feminist themes here and there, a bit on right-to-die, a couple adaptations. My main goal, really, was just to tell a good story, a nice shapely narrative, beginning to end. Not so different from my goal in philosophy these days, as it happens.

But yes, half a dozen scripts have been gathering dust since the ‘80s. Probably deservedly!

That is illuminating—your goal in philosophy is not much different than telling a good story. Writing believable dialogue is notoriously difficult, even for observant, nimble writers. Was it difficult to learn how to write dialogue?

In my extremely limited experience, Hollywood types do often talk just as they’re satirized on the screen—love your script! you’re great! where have you been hiding?!—but then they start in with ‘notes’ about the little things that would obviously need to be changed in your script. I was once told, in such a conversation, that of course this was a problem and that was a problem, the setting, the lead character, the ending, whatever, until I finally asked, in exasperation, so what did you like about it?! Answer: you can write dialogue. In fact, the one tiny paying job I ever got in this area was punching up the dialogue in another writer’s work.

Whether I have any real skill in this area is an open question, based on limited evidence, but for what it’s worth, I’ve never found writing dialogue to be the hard part. If I have a story, if I know what’s supposed to happen in a given scene, and crucially if I have characters I understand, then all I have to do is march them into the room and see what they’re inclined to say. I was once asked to do a rewrite where my protagonist was to be changed in ways x, y, z, and I had to say that if you change the character that much, I no longer understand them well enough to know what they’d say or do. Didn’t help with my career prospects, I’m sure, but it was true just the same.

It seems that your interest in back and forth, conversational exchange, and voices has influenced your philosophical writing. In What Do Philosophers Do?, I noticed you use a technique that’s unusual for a philosophy book but powerful in your hands. Right from the top, you begin to introduce a cast of characters to articulate and explore what most philosophers would call “views” or “theories”. Instead of focusing on the view that our sense organs can give us knowledge, or the view that we can’t trust our senses, and so forth, you describe characters who embody these ideas. Here’s a passage near the top:

[L]et’s begin from a perfectly ordinary point of view, akin to that of the Plain Man, a figure who plays a central role in the thought of the mid-20th-century Oxford philosopher, J. L. Austin. When this fellow, the Plain Man, ‘look[s] at a chair a few yards in front of him in broad daylight,’ he believes there’s a chair there, and though he might not put it this way, he thereby takes himself to have gained straightforward information about the world, to have come to know something about it.5

Throughout the book you introduce the reader to other characters—someone you call the Plain Inquirer, Descartes, Berkeley, Wittgenstein, and so forth. On the philosophical stage you build, your characters act out their parts. The effect is beautiful—abstract ideas become concrete, dramatic, alive. You did this consciously, right?

I’m glad you liked that. I haven’t written much philosophy in the form of explicit dialogue, but I guess I did come away from screenwriting with that device of representing philosophical positions as the views of particular characters, describing their thought processes, and bringing them into engagement with each other. Yes, it now looks as if I’ve been using my old screenwriting method in philosophy for years without noticing: I think my way into a position I want to propose, I do my best to empathize with the other figure or objector, and I see what the two of them would say to each other. I guess that cover image of Beckett and Keaton is something of an answer to the title question: What do philosophers do? Answer: they talk to each other, listen carefully to each other, exchange ideas.

Trying to empathize with a philosophical position by creating a character—that idea seems worth reflection. Something from Bertrand Russell comes to mind: “In studying a philosopher, the right attitude is neither reverence nor contempt, but first a kind of hypothetical sympathy, until it is possible to know what it feels like to believe in his theories, and only then a revival of the critical attitude…”6 Does that process moving from “hypothetical sympathy” to “critical attitude” resonate?

Russell’s advice about ‘hypothetical sympathy’ sounds right to me. Thinking your way into a philosopher’s head means reading carefully, sympathetically, without preconceptions about what they must or must not mean. I feel less confident about the ‘revival of the critical attitude’, which sounds a bit like his own objectively correct standpoint. From Naturalism on, my own approach has been, well, naturalistic or (one book later) second-philosophical, but I don’t think I ever pretended to have conclusive grounds that everyone ought to do as I do. My stated goal has been to describe the Second Philosopher—her beginnings and her progress, the problems that are salient to her, how she approaches them, and the conclusions she reaches—then leave it to the reader to decide if this is a way of doing philosophy that resonates.

Sadly, much of philosophy nowadays seems set in the context of firmly accepted taxonomies; people skim to determine which box the author falls in and to find the point at which some standard objection can be lodged. I get it, career pressure is a visceral motivation, but the criticisms are sometimes so sharp that I want to cry, why are you writing about this person if you think they’re such an idiot?!

Perhaps it takes one to know one? Well, I agree with you about some philosophers’ reading habits—and it’s going to get worse with people now reading AI-generated summaries of research. A twentieth-century Canadian philosopher, Francis Sparshott, had this indictment for his colleagues: “[M]ost members of my profession, I have come to learn, do not read a philosopher’s words to see what he is saying, but only to see which opinion already familiar to them he comes closest to espousing.” Ouch!

Let me pivot to a question that I’ve meant to ask you about motivation. There’s an old line about a professional being someone who can do their best work even when they don’t feel like it. How have you pumped yourself up and pressed on with work when you’ve felt deflated?

I guess I’ve subscribed to the Anthony Trollope school—he’d get up early and write his four pages every day, rain or shine, before his job at the post office. He’s taken a lot of criticism for this—what about artistic inspiration?, what if the muse doesn’t visit?, that sort of thing.

Many people would probably make analogous remarks about philosophy. Of course, I don’t get a fixed allotment of pages every day. Sometimes I spend a whole morning on a footnote that I then delete, and occasionally something throws all the cards back up into the air, and I have to give up on a whole chunk and start over. But I chip away. Maybe what this comes to is that I don’t seem to feel either pumped up or deflated. I just keep trying to figure out whatever it is that I’m so keen to figure out.

Deleting material is something philosophers don’t seem to do often enough. A friend of mine once wrote a full book manuscript on the metaphysics of persons but then got bored and moved onto other projects. Don DeLillo has a fascinating remark about throwing away material:

I used to find ways to save a paragraph of sentence, maybe by relocating it. Now I look for ways to discard things. If I discard a sentence I like, it’s almost as satisfying as keeping a sentence I like. I don’t think I’ve become ruthless or perverse—just a bit more willing to believe that nature will restore itself. The instinct to discard is finally a kind of faith. It tells me there’s a better way to do this page even though the evidence is not accessible at the present time.7

That’s very nice! It’s true, or at least I agree, that it’s satisfying to cut out words and sentences and even paragraphs. There’s the old Strunkian wisdom to “Omit needless words! Omit needless words! Omit needless words!”—though I will occasionally let stand or even insert an extra word or two to maintain a rhythm. More broadly, there’s the imperative to include nothing that isn’t essential to the overall line of thought. I sometimes trick myself by demoting a passage to a footnote. Then, as I gradually realize how much smoother the main text has become without it, deleting becomes easy.

Once, when I was a novice gardener comparing notes with my more experienced mother, I happened to mention that I’d finally brought myself, however reluctantly, to pull out a sad, scraggly plant that I’d been nursing unsuccessfully for weeks. She told me this was a mark of a true gardener—the willingness to get rid of a plant that hasn’t been thriving in a given spot and put in something that will.

Don’t be afraid to uproot your words. I’ve noticed that you read a lot in order to write on your topics. Do you read hardcopy books and printed articles, or do you mostly read on a screen? Do you make notes while reading?

I used to read physical books and photocopies at the desk, propped on a book stand, with two kinds of notes—straight content notes on one sheet, reactions and miscellaneous thoughts on another. (When this was reading for the seminar, there was a third set of notes, derived from the first two, but that’s another story.) Now that physical limitations keep me lying down much of the time, electronic copies of articles work best, with a tablet for note-taking (the two batches of notes are now just in two different colors).

I’m curious about the third type of notes for a seminar.

The third set of notes was a series of discussion questions for the seminar. I’d read through, picking out the line of thought I wanted to highlight in class. I’d have notes for each question, including pointers to the passages that I thought we’d want to inspect, in case no one else hit on them in discussion. (This is where your “show the receipts” comes in—whenever someone offered an answer, we’d ask for a supporting passage and scrutinize the text together.)

Some of the questions were straightforward, to give the younger students an opening to speak with some degree of confidence. (Seminar veterans would instinctively hang back on the easy ones to give the youngsters a chance.) Most of the time I’d have some idea of the answer I expected, but sometimes I’d take a flyer on something in the text that I really didn’t understand and see if anyone had any ideas. Every now and then, the discussion would take a turn and end up in places I hadn’t anticipated, which was delightful when it happened! Often students would ask me to give them the questions in advance, but I’d tell them that anticipating the questions, picking out the important ideas for the seminar topic at hand, was part of the exercise.

What writing advice do you share with graduate students?

Some of what I’ve said so far has been half-answering this question, I think. More specific advice depends on what the particular student needs to hear: some students need to be pestered about matters as ‘trivial’ as punctuation and paragraphing; most need help with the not-so-simple matter of formulating the thesis they want to defend; many need coaching on dividing an argument into steps, keeping material relevant to the current phase of the argument together in a single section, not succumbing to the temptation to get ahead of oneself, to mix in material that belongs elsewhere. There are so many temptations. Students often write three sentences saying the same thing, hoping one will get through, but this just confuses the reader: Is there supposed to be something new in this sentence, what am I missing? Figure out the right way to say it, and say it once. That sort of thing.

Until the gag is chewed fit to swallow or spit out the mouth must stutter or rest, someone might say.

Yikes—harsh advice! I have a couple of stories from my own graduate experience that I like to tell students. I was switching from math to philosophy mid-stream, in a program with many students who’d be studying the subject at a high level for years, so it was a rocky time. My cowardly efforts to slip through the breadth requirements with a lot of math-related courses eventually stopped working, and I ended up in a seminar on personal identity with Tom Nagel. In that course, we were required to write three short papers on purely philosophical topics. Terrified, I drafted my first effort and asked a friend of mine, a fellow student with a firm philosophical background, to read it. She told me candidly that she couldn’t understand what I was trying to say. I replied that I was trying to say blah-blah-blah, which, it turned out, she understood quite easily. So write that, she told me.

The other story is about Nagel. At the time, he lived in New York City and commuted down to Princeton by train. Rumor had it that he read his students’ short papers during the train ride, with all the noise and distractions that would involve. So the grad student scuttlebutt was that we needed to write our papers clearly and directly enough to come through to someone in that challenging environment. I used to share that advice with my students: Write for Nagel on the Train. (A variation, I suppose, on Pity the Poor Reader.)

Wise advice tucked inside good stories. Even after retiring from teaching, you’ve continued to work with graduate students. A friend of mine, Louis Doulas, who got his Ph.D. from UC Irvine, told me he joined your reading group.

Someone once told me that in retirement, you learn which parts of the job you’d do for free. For some years, my graduate seminar was intertwined with my research and writing: I’d put together a syllabus of things I wanted to read more carefully and think about in more detail, and some students—bless them!—would attend whatever the topic and enter into the spirit of the thing. So kicking ideas around with graduate students was something I knew I’d miss. In my last year pre-retirement, I was on medical leave, but one student had been waiting patiently for a reprise of one of my old seminars, so we agreed to meet once a week at my home. The pandemic was looming. As we said our good-byes after our penultimate session, we half-joked that this might be the last time we’d see each other in person. This turned out to be true—our final meeting that term was by Zoom. When we’d signed off our respective computer screens, the sadness of the two of us in our respective isolation made me think that all of us—I mean, me and my seminar stalwarts—could probably use a little fellowship at that scary moment, so I reached out, and that’s how the group that Louis mentioned came to be. We’d talk about whatever one of us proposed to talk about, most often, but not always, a piece of writing we were working on or a line of thought we were developing. The topics varied widely—vision science in the Islamic golden age, medieval heresies behind Descartes’ dream argument, early modern (especially Berkeley), history of analytic, the philosophies of logic, math, and physics, science and religion…—but we all did our best to pitch in even on topics far outside our own areas of concentration. During those early days, I proposed a few dark names for the group (perhaps a bit too much Beckett for the moment), but one of the students came up with ‘the Pen Pals’, which immediately stuck, soon shortened to ‘the Pals’.

The Pen Pals! A friend once told me that Alvin Plantinga used to have a reading group for graduate students at Notre Dame, where they’d read Plantinga’s work in progress, and the students called themselves “Al’s Elves”. Are the Pals continuing to meet?

I’ve thought several times—surely this is the point when the Pals quietly fade away, having served its purpose—but we’re still meeting, now by-weekly, these five years later. The cast has changed from time to time, now no students left among us, and I’m the only one still in Irvine. We’ve drifted into new topics—one former student is now writing about mental representation from the perspective of neuroscience, and I’m leaning more toward technical philosophy of set theory—but against all reason, the Pals persist. And I’m glad of it.

You’ve been using your retirement to write, but what else have you been up to?

I read, obviously. Movies, still. And I guess I haven’t mentioned how much I love painting—Giotto, Sassetta, van der Weyden, van Eyck, Corot, Daumier, Cezanne, von Gogh, Monet, Matisse, Richard Diebenkorn, old Japanese screens and woodblocks. I spend a fair amount of time with my art books.

Oh, and baseball, my hometown Padres.

Does watching baseball give you a break from thinking about philosophy? Or do the rhythms and rituals of the game, or the stats and the stories, somehow intersect—if that’s a good word—with your ideas and your reflective life?

Baseball is a nice break from philosophical work, though it does inspire reflection in its own way—that’s why so many writers write about it.

When I was working on my dissertation, I’d type away all day, then knock off completely in the evenings to watch the Mets game, keeping score in my scorebook, play by play, inning by inning. They were mostly losing in those days, but that was OK. There in Princeton, you could watch the Mets, the Yankees, and the Phillies on TV, so there was almost always a game on at dinnertime.

It seems to me that one of the pleasures of sports fandom is that it’s understood to be entirely irrational. You love your team for whatever reasons that may not add up to much more than that they play for your home town and you followed them in your youth. You have a favorite player on your team, knowing that you might thoroughly disapprove of him if he played for someone else. We fans can agree and disagree and argue, with enthusiasm, while fully acknowledging that much of what we’re saying is just plain bunk.

Do you watch sports, Nathan?

If you had asked two years ago, I’d have said “no”. Got time for a story?

Of course!

Growing up in Canada, I received a pretty standard dose of hockey from skating on frozen ponds, street hockey skirmishes, and the CBC. My grandfather and great-grandmother loved the Toronto Maple Leafs, even through the team’s painful decades of losing. (The Leafs haven’t won the Stanley Cup since 1967—they are hexed, as far as I can tell.) I saw some games at Maple Leaf Gardens and made signs for my favourite players. But during high school, I quit watching hockey. I seemed to be constitutionally uninterested in sports for more than two decades.

Then my daughter got into hockey. We attended a few hockey games and being in the arena reactivated familiar, old feelings for me. My daughter decided her favourite player was Connor McDavid; she asked for an Edmonton Oilers hat and jersey. And of course I started following the Oilers. My family and friends seemed puzzled about how I came to be a hockey fan, but what happened, I figure, is a mix of memory, family, and Canadian spirit.

Why don’t you watch the Maple Leafs?

They’re hexed.

By the way, I agree with you that watching sports engages reflection. There was a poet, Donald Hall, who I think was more famous for his baseball writing than for his poems, and he said of baseball that “the game and the players form a kind of world in miniature in which our whole lives can find their reflection. Birth, desire, copulation, ambition, fame, aging and decay—all the things that run through and animate our lives.” I have no clear idea why Hall included copulation on his list, but hockey is a miniature world for me. The speed and skill of the game is outstanding, but watching teaches me something, I think. Hockey is a game of mistakes, and what you do with a puck after an unexpected bounce is what matters.

Mistakes! In baseball, the best batter fails two-thirds of the time.8

My type of reflection on baseball is less heady than what Hall describes, I think. Just the usual quiet sunny afternoon debates about whether the manager pulled the starter too soon or too late, why the bunt can be a good play despite what the analytics say, how much do or should the Padres regret the Soto trade, the perennial topic of great baseball names (my current favorite is Lars Nootbaar). There’s space between plays that’s naturally filled with… talk.

How have you approached mistakes in your work? We’ve talked a little about throwing out material, but what sort of pivots or reformulations or reinventions have you managed when you found out that something you’ve worked on isn’t right?

In my second book, I flat-out rejected the position defended in my first. It rested on a false premise. Everyone in the philosophical circle I engaged with at the time accepted this premise, so as a young graduate student, I figured I could take it as given and build the case I wanted to make from there. That’s what I did in my dissertation and in the subsequent book. But there was always this nagging worry that something was amiss with that common assumption, so as soon as the book was done, my next project was to examine it more closely—and it collapsed, taking my old view with it. This wasn’t too embarrassing, because so many people more senior than me had made what I now thought of as a mistake; indeed, it still has ardent and accomplished defenders. If I was disheartened, I don’t remember, but it was disorienting because I’d lost the only way I knew of supporting a core belief about set theory that I’d harbored since I first read those wonderful books in the cabinet at the back of Mrs. Risty’s high school classroom. Still, once I acclimatized to the realization that this core belief was wrong, and to the deeper reasons why that was so, it was exciting to see a new, more responsible direction opening up.

So I guess I’d say: if you’re trying to figure something out, surely the best reaction to a mistake is to own it and see where the new, better picture leads.

Who have your best critics been?

I think the best direct critic I’ve ever had was Hartry Field, back in the youthful days of my first book, when (to put it crudely) he was arguing that numbers don’t exist and I was arguing that they do. At the time, many of us in the field accepted the same background assumptions (including the one I soon came to repudiate!) which made local criticisms effective. It was also an unusually collegial group, issuing and receiving criticism respectfully, listening and reacting in good faith. We met often in various configurations over what seemed like an endless series of sessions and conferences. Hartry in particular was a sharp but constructive critic.

Tell me about projects that have kept you busy recently.

Sophia Arbeiter and Juliette Kennedy have edited a hefty volume of essays with replies that finally appeared last year; I particularly enjoyed exchanges with various of the authors as I was drafting those responses. Since then, there’ve been a number of handbook-type chapters, on naturalism in the philosophy of logic and in the philosophy of mathematics, on Wittgenstein’s views start-to-finish and his views of mathematics, on naturalism and skepticism, on set-theoretic method and set-theoretic foundations. But the main project of post-retirement, starting a few years back, has been a return to the topic that got me into philosophy in the first place: how can we find and evaluate new axiom candidates that might settle the continuum problem?

Is that related to your two-part article you published in the ‘80s, “Believing the Axioms”?

Yes, if all goes well, it’s to be book-length successor to that piece: Believing the Axioms, Revisisted. A lot has happened since the ‘80s—in the math, in the scholarship (new collections and translations), and hopefully, in my philosophical perspective (see above). This sort of thing presents a particularly delicate question of audience: a precocious math major, a beginning philosophy graduate student with technical leanings, a grown-up philosopher of mathematics interested in set theory but not immersed, a mathematician curious about foundations, even a set-theorist personally involved in the work. But there’s a compelling story to be told here, and I hope to have the wherewithal to tell it!

After that, I imagine I’ll figure I’ve written more than enough already and it’s time to shut up, but people who know me don’t believe me when I say this. And I have to recognize that they could be right.

Notes

- Penelope Maddy, What Do Philosophers Do? (New York: Oxford University Press), 126, footnote 38. ↑

- Marilynne Robinson, The Death of Adam: Essays on Modern Thought (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin), 1–2. ↑

- Samuel Beckett to Thomas McGreevy, 18 October 1932, in The Letters of Samuel Beckett, Vol. 1: 1929–1940, eds. Martha Dow Fehsenfeld and Lois More Overbeck with George Craig and Dan Gunn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 134. ↑

- David Thomson, Have you Seen…?, Alfred A. Knopf Publishing, 2008, 767. ↑

- Penelope Maddy, What Do Philosophers Do? (New York: Oxford University Press), 2–3. ↑

- Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1945, Chapter 4. ↑

- Don DeLillo, “The Art of Fiction No. 135,” The Paris Review (Issue 128, Fall 1993). ↑

-

Did you see the clips of the Oakland A’s player belting four home runs in a single game? Wowza! I don’t follow baseball, but a friend shared a video.

Yes, I had seen reports and videos of Nick Kurtz’s remarkable game. Not only did he hit 4 home runs, he also went 6 for 6 (6 hits in 6 plate appearances)—and he’s a rookie. He’s from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, home of a large Amish population, so despite the fact that he’s not one himself, they call him Big Amish. 6’ 5”, 240 pounds.

I enjoyed his “butter churning” celebration.