Roy Sorensen’s Workbench

Paradoxes, Magic, & Stealth Philosophy

Some years ago I presented a paper at a workshop where Roy Sorensen was in the audience. After my talk, Sorensen surprised me with a thoughtful gift: an unsharpened pencil. The pencil had inscribed on it a warning: “TOO COOL TO DO DRUGS”. He explained that when the pencil is sharpened down, the “TOO” disappears, thwarting the intended drug-free message. Further sharpenings don’t help.

I have been fascinated by Sorensen’s writing since I was a graduate student. Much contemporary philosophical prose is a variation on a narrow set of stylistic themes, but Sorensen has made a career producing essays and books that subvert expectations and tweak conventions. His sharp, analytically probing writing is animated with enthusiasm about ideas, striking stories, off-kilter jokes, and self-effacing humor. Reading Sorensen’s works, I am confronted with a distinctive human being more than a professional academic. Sorensen is too cool to write dull prose. I once wondered: How could a successful academic philosopher get away with these literary exploits? And where did this all begin? I wrote to Sorensen and we talked about it.

Roy Sorensen is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Texas at Austin and Professorial Fellow at the University of St Andrews. He studied philosophy at the State University of New York at Plattsburgh (B.A., 1978) and Michigan State University (Ph.D., 1982). He has also taught at Illinois State University, University of Delaware, New York University, Dartmouth College, and Washington University in St. Louis. Sorensen’s writing explores puzzles and paradoxes of knowledge, language, and metaphysics.

What sort of books did you like to read when you were a child?

I read inspirational stories of children overcoming challenges such as blindness. This genre made self-pity very difficult. Yet, I overcame this obstacle.

Who was your favourite author?

My favorite author was Dr. Seuss (Ted Geisel). Horton Hears a Who! amazed me with Horton’s discovery of a microcosm on a speck of dust. The poignant illustrations and poetry made me want to speak up for the little people no matter how large their oppressors. I still want to. Maybe one day I will!

Alright, now’s your chance: Will you speak up for the little people in academic philosophy or side with their oppressors?

“ ”1

Before going to college, did you have any experiences with philosophy?

Some of my high school teachers informed me that philosophical poetry goes back a long way. One recommended Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things. I was intrigued by the hedonism. But the absence of pictures was a disappointment.

Your writing often includes short stories. Did you enjoy storytelling when you were a child?

I was mostly a listener, not a talker. Every night, my brother and I secretly listened to Jean Shepherd’s radio monologues in the dark before falling asleep. Shepherd was coy as to whether the stories were fact or fiction. Listeners were wary because Shepherd would entice them into hoaxes. To illustrate how bestsellers lists could be manipulated, he got listeners in pre-Sorensen 1956 to request I, Libertine at bookstores. Demand for the nonexistent book grew so strong that he joined some other ghostwriters to publish a copy, with himself on the cover illustration. Shepherd’s hoax stories inspired me into wiring up the radio with a tape recorder so that I could trick my mother into thinking I was on air doing a monologue. My nonexistent story was an homage to Jean Shepherd’s nonexistent stories. Later, I listened to Spalding Gray, Garrison Keillor, and other storytellers inspired by Shepherd.

How did your mother react to your monologue?

She was pleased by my ingenuity. Mothers disapprove of being deceived by their children. But parental morality gets trumped by the desire to discern some virtue in the ruse.

Tell me about your first experiences writing philosophy.

Writing philosophy was slow and serious in my undergraduate classes. In college, I used a typewriter which made me dread making an error on page one. I tended to stand by what I typed—but not what I said aloud. Freedom from clerical chains made philosophical conversation more honest and rational than writing. Word processors were a moral and rational leap forward.

Back when you started out, did the writing of any philosophers strike you as attractive or worth emulating?

I admired Bertrand Russell’s writing and continue to admire it. I agreed with all of Russell’s criticisms of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s writings. Nevertheless, Wittgenstein’s aphorisms stick in my ear.

What is it about Russell’s prose that you liked?

Russell was clear and witty. As a teenager I would read Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy while waiting for my irresponsible friend to drive me to our job. The friend was chronically late. But the book was so enjoyable that I thought, “Hey, it would be great to spend my whole life reading books like this—and not going to work!” After I got a tenure-track job, my young nephew would be puzzled at my liberty to enjoy daytime activities: “Uncle Roy, you don’t have a real job, do you?” I felt victorious.

Why did you pick up Russell’s book?

It was stocked at my town library in Farmingdale, Long Island. I probably recognized Russell as a celebrity intellectual.

Do you have a favourite Russell joke?

His letters are filled with perceptively amusing irreverencies. Here is a specimen.2

I am looking forward very much to getting back to Cambridge, and being able to say what I think and not to mean what I say: two things which at home are impossible. Cambridge is one of the few places where one can talk unlimited nonsense and generalities without anyone pulling one up or confronting one with them when one says just the opposite the next day.

Talking unlimited nonsense—I suppose Cambridge hasn’t changed after all the years. Did you ever try out jokes in your early papers?

The humor began systematically with Wittgenstein’s remark at Philosophical Investigations 111:

Let’s ask ourselves: why do we perceive a grammatical joke as deep? (And that is what philosophical depth is.)

I cultivated the ordinary language philosopher’s ear for incongruity—and eventually wrote a dissertation on G. E. Moore’s odd sentence ‘I went to the pictures last Tuesday, but I don’t believe that I did.’ Wittgenstein’s suggestion was that the surprise in Moore’s sentence was due to a violation of a rule and so evidence of that rule. I was interested in the formalization of natural language by linguists, logicians, and artificial intelligence researchers. I started to use jokes when teaching logic—especially Lewis Carroll. I borrowed heavily from Peter Heath’s The Philosopher’s Alice and Martin Gardner’s The Annotated Alice.3 My M.A. thesis was titled The Depth of a Grammatical Joke (which reincarnated as the penultimate chapter of A Brief History of Paradox). My first published article, “Pragmatic Paradox Liable Questions,” was based on questions like ‘Are you asleep?’. They contain a pragmatic paradox in their set of direct answers. The questioner is not hoping to learn the answer by the testimonial affirmation of ‘I am asleep’. The answering machine paradox—‘I am not here now’—is similar.

Can you remember any important writing advice you got when you started submitting papers to journals?

Be attentive to both good and bad referee reports. The bad reports warn you of misinterpretations that you failed to forestall.

Academic writers complain about poor referee reports, but the advice you received frames even a terrible report as a learning experience. What lessons did you take away from reports in your early years?

One lesson was to settle questions of interpretation by asking the author whose work I engage. (Email supercharged this advice.) Between me and the author is always this other guy: the straw man. Getting past that guy generally requires more than passively listening to the author. Actively formulate the author’s view and have the author listen. Skip any politeness that the author may have bestowed on the target of criticism. Plain, short sentences are easier for the author to grade as distortions.

In the end, there might be another straw man. But a better one—and sometimes better than both of the real people in the dialogue.

What you say about settling questions of interpretation reminds me of The Library of Living Philosophers. The series was started in 1939 and, as you know, each volume showcased the work of a major figure: Dewey, Moore, Russell, and so on. Critical commentators and interpreters would respond to the eminent author and then the author would reply. What’s interesting is that the founder and long-time editor of the series, Paul Arthur Schilpp, once said that the project was a big failure. Here is a report about what Schilpp said during a lecture at Saint Louis University in the early 1980s:

Schilpp gave an informal, zestful, and, I felt, uncommonly candid description of the decades of work he had devoted to editing the Library of Living Philosophers. He explained to his audience that the idée directrice for the project was his early belief that if only a philosopher, during his own life, could respond to his critics, much philosophical misunderstanding could be avoided, and the development of the discipline would be encouraged.After a lifetime’s dedication to this idea, Schilpp made two observations which carry, I believe, a great deal of sting. For, he said, he would not now undertake the project of the Library of Living Philosophers in the light of what he has learned about the profession and the practitioners of philosophy. With the single exception of one philosopher [G. E. Moore], Schilpp has not encountered others who have been able or willing to admit mistakes. It was clear that Schilpp was not proposing that in philosophy we discover a tradition of two millennia in which only perfect, error-free thought is to be found! What seemed to him suspect and hard to accept is a certain stubborn pride, found in us all, but not to the extreme he has found it in philosophers.Schilpp went on to give his second reason for judging that the idée directrice of his life’s work has been illusory. As precisely as I can remember his words, Schilpp said he has come to see that “philosophers do not want to understand one another.” They do not wish to communicate. They are concerned only with their own private, personal sets of beliefs.4

Any reactions to Schilpp’s pessimism?

Wow, that does sting! Not even G. E. Moore matches the mathematician Martin Gardner’s practice of appending errata to every article he wrote.

I do remember one eminent philosopher who grew exasperated at my logic-exercise-style efforts to spell out his enthymemes: “If my argument could be correctly stated that way, I would have already done it that way.”

Possibly, Schilpp’s setting was too formal. During colloquia, speakers give their official line. Peer disagreement is irrelevant. The speaker asserts on the basis of their own evidence. There is no averaging out. But then the speaker goes out to the bar and loosens up. The speaker is more candid and open to advice about repairs. Maybe if Schilpp spent more time in bars, he would change his mind.

The Tavern of Inebriated Philosophers is a depressing place to imagine. Some visitors to the tavern might get in a drunken brawl. But, yes, I agree with you: The formalities of a collection of critical essays written for posterity could well induce less flexibility and less humility among participants than would be desirable. It’s a public performance with higher stakes than any colloquium session. But do you agree with Schilpp that philosophers are not inclined to understand their opponents and revise their ideas?

My guess is that Schilpp is missing unacknowledged changes of mind. Belief is involuntary, so minds change regardless of verbal behavior.

Kant denies he changed his mind when issuing the B edition of the Critique of Pure Reason. He says the difference is only an expository improvement over the A edition. But there are many changes, mostly improvements.

In an interesting contrast, the poor reception of the Treatise led David Hume to informally characterize its doctrines as juvenilia. This was made official in his notorious 1775 “Advertisement” that told readers to rely solely on the Enquiry (and which the publisher agreed to insert in future editions of the Treatise). Only a minority of Hume scholars continue to follow Hume’s instructions. Many go as far as deny there are any substantive differences. They cite remarks in which Hume seems to concede the difference is only expository.

Hume’s publisher may have thought the “Advertisement” good salesmanship. Hume reacted to the failure of the Treatise by gradually educating his readership. He poured old wine in new, diluted bottles. The Treatise ruined Hume as a prospective academic. To keep philosophizing, he had to live off his books (never done before!).

Yes, I’m sympathetic to the idea that a philosopher’s ideas sometimes evolve without the philosopher acknowledging the changes. But I think Schilpp can embrace that point and continue to feel as though he wasted his time on The Library of Living Philosophers. After all, if we assume that authors are prone to change their minds without recognizing those changes, why would Schilpp expend energy arranging for them to discuss their ideas, identify the correct interpretation of texts, and so on? I mean, I suspect the assumption that there are unacknowledged or unrecognized changes of mind could ignite Schilpp’s pessimism, too. What do you think?

I think it more likely that philosophers know about the changes (Kant) or lack of changes (Hume). If Schilpp wants to be depressed about shortfalls in intellectual honesty, well, that’s a late lesson to learn. If he wants to promote philosophical improvement, keep on facilitating objections by critics.

Consider couples. They continue to argue even if they do not expect acknowledgements of changes of mind. What is important is the change of mind, not the acknowledgement.

You changed my mind, but I’m not going to acknowledge it. Have you ever benefitted from acknowledging changes in mind and mistakes?

When interviewing for jobs years ago, some well-wishers speculated that I was too frank in admitting mistakes and ignorance of relevant scholarship. At the University of Delaware, I gave a job talk in which I proposed a definition. Most of the discussion went along foreseen paths. But then David Cole asked whether the definition was really a sufficient condition. When I began to concede it was not, the other faculty began throwing life preservers. None floated. I just had to express the hope a better life preserver was out there somewhere. Embarrassed silence… Finally, Cole raised his hand: Is it really a necessary condition? This was followed by another rescue mission and the same result.

The following week I learned that I got the job!

Now there’s a life preserver! So, I was wondering: Before you had job security, what did your parents make of your decision to become a philosopher?

They were alarmed by the prospect of me overeducating myself into unemployment. I grew up in a Wittgensteinian paradise in which there was no philosophy nor any danger of anyone in my family understanding any philosophy. Except me.

Did you receive any mentoring in graduate school?

The first I heard of ‘mentoring’ was being asked, as a professor, whether I wanted to mentor a student. I did get advice as a student and was told piecemeal how to behave as a teaching assistant. But I do not recall systematic counsel. My recollection was that university students considered themselves as adults and would have resisted systematic rearing into the profession. Anti-paternalism certainly was handy when I turned down many wise suggestions.

The job market was awful when you graduated in 1982, and the American Philosophical Association sent out warning letters. One letter from around when you received your Ph.D., written by Ruth Barcan Marcus, said this: “While we cannot predict the future availability of academic positions in philosophy with precision, we expect that in the 1980’s the number of persons seeking such positions will remain much greater than the number of academic positions available.”

The APA was responsible to warn of a terrible job market. I had assumed that the maxim ‘Publish or perish’ was an exclusive disjunction—true only when one of the disjuncts is true. So I tried publishing after two years in graduate school and eventually succeeded. But then I learned some philosophers doubted there was an exclusive ‘or’. There is only the inclusive ‘or’ of the truth-table—true when either or both of the maxim’s disjuncts are true. Damn!

Yes, we academics sometimes publish and perish. Is there a better way to think about the job market than that maxim?

The job market is a lottery in which participants can buy more tickets with their research, conference going, contacts, and so on.

What happened after graduation?

I had to settle for adjuncting as my grad school funding ran out. But I kept buying more tickets. Through a sequence of lucky wins, I eventually got a job a tenure-track job at NYU. But it was not as though destiny was pulling me toward Greenwich Village. I could have joined the other philosophers who could not find academic jobs in the 1980s and are now millionaires from other careers.

Where did you adjunct?

I adjuncted at La Roche College in 1983, teaching logic and medical ethics.

What did you do between graduation in 1982 and La Roche the next year?

I began a book entitled Blindspots. The blind spot of the eye is located where the optic nerve connects to the retina. Nothing can be seen from this spot but the visual system fills in gaps on the basis of the rest of the scene. That spot became my vantage point on a panorama of paradoxes: the surprise test, the iterated prisoner’s dilemma, the sorites, and more. There is much to fill in. So, despite my love of philosophical quickies, I wound up writing a 450-page book. The book was about slippery slopes—and became one.

What gave you the idea to start a book, rather than prepare more journal articles? You didn’t have a job in ’82 and you must have known the book would take years to complete. Is there a story?

The book was to be written regardless of whether it helped (or hurt) getting an academic post. Instead of getting a non-academic job, there was the option of becoming a trophy spouse. I married my first wife down in Austin, Texas. She is there now. We are still friends. Indeed, we are colleagues… And still married.

Are you still a trophy spouse?

Trophy spouses devolve into atrophy spouses. I try to outswim the process.

Back to those lottery tickets: On your CV, I count seven publications by 1982. Several more articles appeared in ’83 and ’84, so I figure at least a few of those post-graduation papers were accepted when you were still a Ph.D. student. Was the early flurry of publishing activity part of a strategy to get a career? How were you thinking about this at the time?

I was vain and unrealistic enough to try to publish. When I succeeded, faculty were congratulatory. My dissertation director, the logician Herbert Hendry, had a way of encouraging students by first making them an appropriate object of ridicule and then ceasing his withering objections. There would be this silence. And then Hendry would say, “Well?”. That was the go sign.

Hendry did not like wasting time. That probably encouraged me to package issues into paradoxes. I could be in and out of his office in 15 minutes.

Paradoxes have been a staple in your philosophical diet for years. Where did your interest in them begin?

Even before the dissertation project on Moore’s puzzle, I was drawn to paradoxes because they made philosophical problems compact and well-motivated. For instance, when challenged to explain why self-deception is puzzling, I could compress the vague issue into three plausible propositions that are jointly inconsistent:

- Person A deceives person B into believing proposition p only if A lacks a belief that p.

- A deceives B into believing p only if B believes that p.

- It is possible for the deceiver to be identical to the deceived, i.e., possibly A=B in the above.

Then I could classify each solution as an attempt to regain consistency by rejecting a component. This compression helps me teach philosophy to students who find the issues amorphous. The issue fits on a one-page handout.

Capturing a philosophical problem as a set of inconsistent claims is helpful in the classroom. But paradoxes and puzzles feature so centrally in your writing, going back to your first publication. This isn’t merely about teaching, right?

The puzzles were a way into the fascinating clouds of philosophy. Wittgenstein tried to condense a cloud of philosophy into a drop of grammar. But I wanted drops that miniaturize philosophy, not eliminate it. Inconsistent triads, fashioned with an eye on the history of philosophy, explain what philosophers are up to. They open a door to people who are interested but bewildered.

I’ve noticed you have “an eye on the history of philosophy.” You aren’t a specialist in the history of philosophy, but you often examine ideas from dead philosophers, greats and lesser knowns, from pre-Socratics and on up through the ages, ones who hail from North and South, East and West. What fuels your study of philosophy’s history?

History was my initial way of understanding philosophy. I was like a dog who wanted to be part of the discussion. History enabled me to participate passively. I could understand enough to make out what was being said. But to participate actively, I needed to compress and focus.

Tell me about your first experience at a professional conference.

The first APA meeting I attended turned me against formal academic style which is especially difficult on the ear. The APA presentations were read manuscripts, followed by read replies, followed by read rejoinders. The issues were too slowly developed for me to sustain attention. As a student, I had to train myself to read big articles by first reading discussion notes in Analysis and Mind.5 I resolved to never read out a lecture. The closest I came to breaking my resolution was when a speaker requested I read aloud his lecture when he could not attend. I instead did a séance in which I channeled the spirit of his laws rather than the letter…

The yearly APA conferences host Symposium and Colloquium sessions, but they ought to add Séance sessions. That could help many speakers discussing the history of philosophy.

Psychics did claim to channel philosophers such as Plato. The nineteenth-century British ethicist Henry Sidgwick, as the president of the Society for Psychical Research, was suspicious that Plato could have forgotten so much philosophy. Professor Sidgwick resolved to come back after his death and communicate if he could. To prevent fraud, Sidgwick left secret codes which he would announce to authenticate his presence. The absence of any code breaking suggests that the methodical Sidgwick did succeed, albeit negatively, in providing some testimonial evidence after his death—absence of testimony is his testimonial to absence. But this is a small sample. The APA could provide more evidence by encouraging members to emulate Sidgwick’s encryption strategy.

I nominate you to head up an exploratory APA committee on Séances in Philosophy. Will you accept?

Only post-mortem.

I had wanted to say just a moment ago that you aren’t the only one to encounter professional boredom at the APA. Don DeLillo once wrote that “longing on a large scale is what makes history.” Arguably, boredom on a large scale is what makes a professional philosophy conference. Were your experiments with different forms of writing in part a reaction to the standard scholarly style?

Boredom is tricky. Instead of correctly diagnosing ourselves as not understanding, we project on to the speaker. The speaker is boring!

At the APA, I did realize there was something interesting in the complicated presentation. And I interpreted the commentator as finding an interesting difficulty with the main essay. I was just frustrated by the gratuitous inaccessibility. When I talked informally afterward, the speaker generally did a nimble job at explaining. The speakers were good explainers stuck in an unfortunate formal format.

Earlier, you said that Paul Arthur Schilpp might have done well to spend time at the bar.

I think everybody has trouble understanding written language when they take it in by ear. It gets worse when the listener cannot interrupt with clarificatory questions. Conversation in a small group is where we shine.

Let me jump to a topic that’s not unrelated: you have written dialogues. The first time I ever encountered your writing was in “Faking Munchausen’s syndrome.” Munchausen’s, also called a factitious disorder, is a mental illness in which a person fakes or induces some kind of medical condition or injury in order to draw attention to themselves. Your piece is written as a set of short letters between a doctor treating a patient who appears to be faking Munchausen’s and an insurance adjuster who repeatedly rejects the doctor’s insurance claims. The doctor and insurance adjuster correspond over whether it’s really possible for the patient to fake having Munchausen’s. How did your interest in dialogue begin?

My interest in dialogue was prompted by notes that Bas van Fraassen sent me. This was when I was a grad student, before email. At first we corresponded with formal letters. But one day he just sent me notes for a letter rather than the formal letter—perhaps by mistake. Van Fraassen’s notes were in dialogue. There were points that could have been in monologue. The dialogue was more illuminating, however. Although I could see how the tracks could have been covered by a tidy letter, that would have wiped out the motivation for the formulations.

You mentioned your exposure to radio storytellers like Jean Shepherd. I am struck by how much of your work blends philosophy with storytelling. In another dialogue, “Fictional Theism,” you develop a character, Ludwig Feuerbach Junior, who argues that since fictions are real and God is a fiction on his view, he counts as a theist and should thus be welcomed into the membership of the Scientific Creationist Society. For your characters, do you try to conjure up a distinctive ‘voice’? For example, did you read some Ludwig Feuerbach and channel some of the language into Ludwig Jr.?

Yes, I try. Ludwig had a German accent.

When I read about Socrates’ inner voice (which only says “NO”), I became leery of my voice of conscience. Even prior to checking reliability, Socrates obeyed the voice—and continued to follow the voice even when it discouraged him from speaking against a contemplated massacre by his fellow citizens. I still listen to my voice of conscience. But I tune it up so that it sounds like the Munchkin Mayor in The Wizard of Oz.

Your Munchkin voice of conscience is slightly disturbing to me.

Psycholinguists studying phonological loops reinforce the commonsense suspicion of heeding “voices in one’s head.” Silly voices are also appropriate for intuitions. ‘If you know, then you know that you know’ sounds plausible in mental baritone but not falsetto. Intuitions may be correct but any basis for thinking so should survive the silly voice test.

Ultimately, Socrates takes the absence of inner “NO” to show that an action is permissible. No “NO” means yes. This suggests Socrates hears inner silences. Hearing silence is not the same as not hearing. The deaf cannot hear silence.

Yes—absences figure into your work over the years. How did you get interested in nothing?

Achille Varzi first interested in me in nothing via the small nothings of holes. He and Roberto Casati elaborated on the David and Stephanie Lewis’s dialogue “Holes.” Varzi and Casati presented a cheerful but sophisticated topology. Their holes are abstract. My holes are concrete. The holes got bigger and bigger, like “The Heavenly Pit,” a massive sinkhole in China. Scaling up absences to possible worlds eventually leads to the question Martin Heidegger called the most fundamental question of metaphysics: Why is there something rather than nothing?

After my spatial expansion of absences came a temporal expansion. I was particularly intrigued by how in the fifth century BC, there was a pivot from being to non-being in China, India, and Greece. That was the historical mystery that prompted me to write Nothing: A Philosophical History

Are there other possible expansions in your quest for nothing? What is the future of nothing?

I am hoping that Hollywood will make the void famous by casting it as a monster. C. B. Martin would suppose a beach ball sized void immaterializes in his classroom. The ball heads toward you. Should you duck? If your head is enveloped by the void, you will suffocate, your blood will boil, and so on. What frightens you is not what the void does but what it fails to do. Voila—visceral causation by absences!

Over the years, I’ve been in a few faculty meetings where that void ball would have been a welcome distraction. Your books and articles feature tales and quotations from fascinating and unusual sources. I find in your work examples that I’ve never seen other philosophers use. I wondered whether you use a notebooking technique, maybe like Ralph Waldo Emerson’s, to catalogue materials you find in your travels. Emerson kept quotations and ideas in many notebooks and then created an index of his notebooks, so he could quickly look up material on a theme. What do you do?

I formerly kept notebooks, although not as methodically as Emerson. Then I tried to immediately incorporate anything new into a draft of something that might become publishable. For instance, I am now pining for a way to insert this fact into something that might see print: Saint Andrew is the patron saint of Russia—and of Ukraine!

Another fact (or perhaps “fact”) comes from the literature on why golf was really invented in St Andrews—pretty close to their Golf Museum. Other countries admittedly had games in which one hits a ball with a stick. But they were missing something: the hole! I regret learning that too late for insertion into the Nothing book!

You say you formerly used notebooks and presumably you now use computer files. How do you file your trinkets away for future use? Is there a method to your filing system?

My notes are in computer files but not organized by topics like John Locke’s alphabetized commonplace book. My notes are injected into handouts for lectures and the beginnings of essays that are rarely finished. I remember them like friends, with memories and “memories” of what prompted them. I suspect many of the memories are confabulated, like my memories of classes that I enjoyed teaching. When I reminisce to former students, they gently note that the classes’ rosters are historically impossible. I pack the class with students from different years.

A fair number of preliminary essays were completed in a shortened, popularized form for A Cabinet of Philosophical Curiosities. They are little Peter Pans that refused to grow up. But the vast majority will be all too reminiscent of human reproduction. So many fertilized eggs, so few maturations. I suspect some will think I should be more enthusiastic about deliberate abortion.

I heard a story about one philosopher who published an essay even after he admitted a fatal flaw when presenting it at a colloquium. His defense: “My articles are my children!” That level of protectiveness goes too far. But it is difficult to muster the ruthlessness with one’s ideas that is rationally warranted. I have met a few philosophers who do seem to have this detachment. They do not publish much!6

Do you typically try out new ideas in conversation before starting to write? Or does writing help you formulate a thought before conversation?

Yes, I try out quick ideas at the open office door of colleagues. My rule is to stand, not sit… I want them to keep their doors open.

Does your own door stay open or closed?

Covid got me to close the door and make appointments for walks—like Aristotle.

Do you offer your students any advice for writing well?

Try to explain the idea to a roommate or, better, present it informally in class. The exercise pares down jargon and exposes what technical terms are crucial for the issue.

What advice do you give students about publishing?

“Give Up!” That’s what your mom says. She is an actuary. If you had a publishable idea, it would have probably already been published. Even if you do publish, it is likely to be among the majority of publications that hardly get read.

If you persuade your mom that you will not give up philosophy and instead make her some grandchildren, then her second best advice is to model the process as a lottery. The tickets have biases toward being picked. Many of the biases are in an unknown direction. So there is some information to be gleaned from the results. But it is difficult for human beings to extract. The practical recommendation is to submit a variety of manuscripts to journals and draw statistically detached lessons from the outcomes.

But your mom thinks this advice will only work at the margins. To complete a publishable article, you’ve got to commit. So your manuscript will become one of your children. But, damn it, not one of her grandchildren!

Family planning is difficult to think about rationally, so thank goodness for mom’s actuarial wisdom. But her advice may lead her child to quit trying and go to the bar—talking philosophy, not writing it. Your advice to students is to commit in order to play the journal-submission lottery and to not necessarily take rejection personally when their tickets lose. Fair enough. It’s good to inform students that rejection is the norm and also emphasize that rejection doesn’t always happen because a paper is unpublishable. But how do you drum up commitment in view of poor odds and disappointments? Let me put it this way: From an early-career academic’s perspective, you are a Powerball lottery winner, but you’ve bought many tickets, including ones that languish in file folders. Do you have any stories of rejection and perseverance to inspire or console?

I don’t encourage when the discouragement is rational and proportional. I may note that failure is a risk for any ambition. And it is worth thinking about what kind of failure one might become. As a teenager, I had an ambition to become a great chess player. Failing at that is terrible because chess makes you narrow. The hours spent on it do not connect to other questions. It is an encapsulated domain. But philosophy connects with many questions. Failing to become an academic philosopher is a more attractive backup than most other failures.

How inspiring!

It is an engineering point. One notches beams to ensure they break at the least damaging point. One builds a house that will gracefully deteriorate. One budgets for breakage in construction. Every success is the tip of an iceberg of failure. When complimented on how many books I have written, I invite my listener to consider all the books that I failed to write.

At about this stage, the student realizes I am also a failure as a guru. Any expertise I have must be primed by details. Professors have useful pointers when their expertise is cued up by the context. Pull them out of context and then their remarks match baseline educated people. Valuable, but not nearly as valuable as appropriately stimulated experts. So the student gives me a draft essay and asks for comments in context. The next day we take a walk and talk about specifics, and the sea, and the sky.

What might a philosopher-in-training keep in mind when trying to blend ideas and arguments with fun and comedy?

Do what comedians abhor: explain jokes. For a nice explanation is that the joke involves a counterexample to an otherwise attractive principle. The essay “Ducking Harm,” co-authored with Christopher Boorse, has this structure. Philosophers want the explanation.

The article begins with this joke: “Two campers, Alex and Bruce, meet a ravenous bear. As Alex grabs his running shoes, Bruce points out that no one can outrun a bear. ‘I don’t have to outrun him,’ Alex replies. ‘I only have to outrun you.’” Then you and Boorse explore puzzles raised by ducking in contrast to sacrificing. People believe Alex can legitimately run away from the bear, leaving Bruce as bear food, even though they would judge Alex as blameworthy were he to immobilize Bruce and feed him to the bear. Alex is allowed to duck but not to sacrifice Bruce. Part of what makes the article funny to me is the many permutations of duck/sacrifice cases, including this one: “In an era of faculty cutbacks, one may save one’s job by writing faster, but not by burning one’s colleagues’ manuscripts, even if they are worthless.” Publish or pyro.

OK, so now I have a question about this 20-second video clip:

Do you blame the jerk bison?

Yes, the jerk bison has clearly failed to read to the end of “Ducking Harm.” In the “Sinking Boats” case, two boats try to capture the attention of a helicopter that can only rescue one boat. Members of each boat are permitted to increase the height of their aerials. Both are forbidden from sabotaging the other’s aerial.

Your case is instructive, but bison literacy is stuck at an all-time low.

William Bennett, the philosopher who was the U.S. Secretary of Education during the Reagan administration, had a character, Plato the Bison. As the oldest and wisest, Plato the Bison was responsible for reading stories from the Book of Virtues to children Annie and Zach. That was back in the late 1990s and early ’00s. I did not watch the PBS videos to the end and so should not cast stones.

Part of what I find enjoyable about your work is not merely the jokes and amusing quips but your use of conceits. Take your essay on Adam Ferguson as a case in point. As the piece opens, you’re walking with a friend in a graveyard in Scotland and you find a curious epitaph that praises Ferguson’s philosophical works, which will, says the epitaph, “long continue to deserve the gratitude and command the admiration of posterity.” But you or your walking partner had never heard of Adam Ferguson! The piece becomes a reflection on self-defeating epitaphs. You have a knack for placing philosophical issues in extended literary frames. When did you start to experiment with that type of writing?

The conceits may stem from my preference for stealth philosophy. Talk about something that does not seem like philosophy and have the audience realize belatedly that they are doing philosophy.

Who are the great stealth philosophers?

Plato, David Hume, William James, Richard Smullyan, William Lycan. These camouflaged owls of wisdom get past defensive bracketing of philosophical ideas. The brackets get erected after children fail to make progress on questions such as ‘Does time have a beginning?’ and ‘Is there an edge to space?’. More brackets get erected when non-philosophers use ‘philosophy’ as a label for issues that cannot be profitably pursued. Stealth philosophers side-step this conversation blocker. They show the continuity of philosophical beliefs with other beliefs. For instance, the stealth philosopher of perception will just presuppose the visible objects must emit, reflect, or refract light—as if it is just common sense or well-established science. They will then have students count the punched holes of the handout or the shadow cast by that handout. These anomalies make the students say “Hey, wait a minute!” and then dis-inter the presupposition from the common ground of the conversation. The stealth philosopher knows where bodies are buried. After students dig some up, they tread with more geological awareness over the surface of daily life.

How do you engage in stealth philosophy when the audience is philosophically savvy? They know where the bodies are buried. Can you still catch them off guard?

Yes, because the philosophers still need to presuppose much. They must inhibit default patterns of thinking, such as attributing knowledge (when belief suffices) and attributing intention (when coincidence suffices). Since they cannot always be on their toes, they sometimes fail to notice some camouflaged philosophy. Bertrand Russell once asked G. E. Moore whether he ever lied. Moore said yes and Russell concluded that this was the only lie Moore ever told. Saul Kripke chided Russell for failing to notice this is an instance of the liar paradox. Others pictured Russell as the stealth philosopher, planting the liar paradox in a compliment to Moore.

I have sometimes been surprised by a stealthy cross-examiner. During a Q&A period at Oxford, Jonathan Dancy just asked me a sequence of mild, clarificatory questions to set up the main question. There was no main question. For my quick answers constituted enough for a syllogism whose conclusion was the negation of my thesis.

By the way, my daughter says that the camouflaged owl is adorable. You could be the camouflaged comedian of philosophy. Do you have any experience in stand-up comedy or theater?

No, though I wish I had tried theatre. As a kid, I liked to do magic tricks for friends.

Is the insightful examination of puzzles and paradoxes a form of magic?

Seneca compared the horn paradox (It is not the case that you have lost the horns on your head, therefore, you have horns on your head) to the cup and dice trick (in which slight of hand deceives the audience as to which cup covers the die).7 The trickery can be a simple equivocation or a fancy amphiboly. When sophistry is signaled, the resemblance to a magic show is strong. There is a license to deceive. The medievals would motivate with deductions that had conclusions that insult the student. Here is Walter Burley’s (1275–1344) favorite:

Whoever says you are an ass says you are an animal.

Whoever says you are an animal says something true.

Whoever says you are an ass says something true.

The premises are undeniable. The student can only avoid the demeaning conclusion by finding a fallacy. William Heytesbury’s (1313–1372/73) Sophismata Asinina is a compilation of 37 sophisms, each concluding, “You are an ass.” I tour this medieval pedagogy in “Teaching by Insult.”

Can non-sophistical reasoning be like magic?

Yes, in contrast to sophistry, paradoxes resemble self-working magic. Instead of trickery, the presenter follows a procedure to yield an outcome that strikes the audience as magical.

The magician’s oath forbids revealing secrets—except to fellow magicians and those who pay much more than the price of admission to the magic show. But, as a teacher, I sincerely try to elicit an explanation from the audience of the sophistry, pass along my proposed solutions, or admit I am stumped. Seneca says we lose interest as soon as the trick is understood. But his own example of the horn paradox is refuted by the interest linguists and philosophers continue to take in presupposition. The feeling of understanding can extinguish interest. The Stoics were chronic sufferers of premature explanatory satiation. But the late medieval logicians were not so abrupt. Nor was Russell.

Let me ask about something I’ve noticed. You use contractions infrequently in your books and articles—and even in our conversation here. Do you have a policy for using them? I have a vague hunch. Sometimes, the lack of contractions gives your writing a kind of seriousness or even formality that catches the reader unprepared for the funny bits. Is that part of your thinking? Dressing up a joke in serious, precise language can be amusing. The reader isn’t ready for staid, meticulous sentences to swerve them into laughter.

I had an English professor who raised the question of when contractions are permissible. After reviewing the complicated rules of others, he suggested that contractions be forbidden except when in labor.8 I adopted his simple rule. Maybe my fidelity was sustained by the contrast effect you mention.

Do you have any favourite comedians?

I like Steve Martin. He started out with magic. His biography Born Standing Up is detailed about the difficulties of stand-up comedy and the mystery of why some comedians make it. I suspect they have to train the audience and then hope for a contagion of popularity to pull in newcomers.

I picked up Steve Martin’s book, by the way. Like you, Martin was fascinated with Lewis Carroll. When Martin was a philosophy student in the ’60s, he took some logic courses at Cal State Long Beach. “The comedy doors opened wide,” he wrote, “and Lewis Carroll’s clever fancies from the nineteenth century expanded my notion of what comedy could be.”9 Has comedy expanded your notion of what philosophy can be?

Yes! Like Martin, I was impressed by reductio ad absurdum. Logical paradoxes fit Henri Bergson’s characterization of humor as robotic loss of agency. One follows an argument to its logical conclusion. An argument is a train than that one must keep riding after one misses the opportunity to exit the premises. Arthur Schopenhauer scolds those who treat it as taxicab that one can enter and exit at will. This loss of will constitutes detachment. Humor provides the same respite from suffering as aesthetics and science. Rather darkly, Schopenhauer thinks gallows humor expands our capacity for suffering by making our own suffering an object of amusement.

Wittgenstein’s “depth of a grammatical joke” passage also suggests that comedy opens doors to linguistics. A classic example is James McCawley’s book Everything that Linguists Have Always Wanted to Know About Logic (but were Ashamed to Ask). Analogies between language and pictorial representation suggest purely visual humor can open doors to art. David Macaulay’s Great Moments in Architecture has a joke illustration of people in the distance discovering the vanishing point of a railroad track. Music also resembles language. Joseph Haydn’s Opus 33 is popularly called the “The Joke” because its false endings trick people into premature applause. Some musical humor is disparaging as when Claude Debussy mocks Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde in “Golliwog’s Cakewalk.”

Do you listen to music while you write?

Only when I need to mask noise and cannot mask it with white noise. And then only instrumental music. And not the sort that makes bids for attention or draws me into emotional reverie. I heed psychologists’ warnings about our poor multi-tasking

So I assume you like phone Muzak, including “Opus Number 1”.

I love the phone Muzak! Maybe I’ve heard it while waiting on hold. But this is the first time I listened to it as a piece of music designed not to be listened to. I tried music designed for concentration. But often it is too assertive: THINK!

Since you live in Texas, land of country music, you should try out this song while you work:

That is a musical analogue of circular argument! I love lakes and New Mexico and so was slow to pick up on the repetition. The same happens when I hear arguments that agree with my convictions.

Purer would be purely instrumental music for a conclusion. There is already much repetition in serious pieces. Syntactic repetition is easy. But there is not enough semantics to express a proposition. Listening to instrumental music resembles looking through a kaleidoscope. The spectacle is meaningless. Nothing is represented. Or nearly nothing. There may be a little reference by musical quotation as when Charlie Parker quotes Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring during his jazz solo in “Repetition”. But that is not a proposition. So maybe instrumental music cannot beg the question or reason in circles.10

Where do you write these days? I assume you are not parked out by that lake, 80 miles from Santa Fe. Is the place you write important?

Presently I do most of my writing back in my office. I have returned to regular lap swimming. To use the campus outdoor pool, across the street from my office, I get in early so that I do not need to use sunscreen. During Covid, I used my home office—which has many distractions.

What are the distractions at home?

I am at my home office right now. I’m trying to complete a tardy email. But I just heard a squirrel on the roof. Did you know that squirrels are one of the leading causes of house fires? There must be a branch within leaping distance of my roof. I’d like to finish the email but I’d better get a ladder and cut down that branch!

Errata

In our conversation, Sorensen mentioned “Martin Gardner’s practice of appending errata to every article he wrote.” But that was a mistake: Gardner did not write errata for some of his articles. Sorensen reports that he was carried away by admiration of Gardner into an error about Gardner’s errata.

Notes

-

Do you mean to say nothing in response to the question?

Yes, you can quote me on that. Well, maybe linguists would deny you can quote me on that. For what is the that?

Could you say more?

In an article, “Empty Quotation,” I argued that “ ” is a counterexample to theories of quotation that require the content of the quotation to be displayed. Paul Saka replied that linguists would deny empty quotation is possible. Spoken language is primary. Written language is just a record of spoken language and is not itself language—contrary to what philosophers of language presuppose. For instance, John Searle confines himself to written speech to skip all the complexities of phonology. In my article, I appealed to empty quotation in programming languages (which offers conveniences comparable to { } in set theory). Saka thought linguists would not be persuaded given their dismissal of writing as language. Saying nothing is more controversial than it sounds. ↑

- Letter to Alys Pearsall Smith (1893) from The Selected Letters of Bertrand Russell, Volume 1: The Private Years (1884–1914), edited by Nicholas Griffin, 25.↑

-

Professional philosophical writing tends to be decidedly unfunny, but I often laugh when reading your work. (Not because the arguments are bad!) Whose writing makes you laugh?

I do not read just for laughs. But it sweetens the prospect of going through the hard work of understanding the linguistics beneath William Lycan’s treatment of the performadox, Arthur Prior on logical connectives (on non-connectives such as Tonk), and Alastair Norcross parrying ridicule of utilitarians. Timothy Williamson is also seriously funny, albeit at a more measured pace. Wittgenstein should be funnier, given his respect for grammatical jokes. But he is far better at explaining how Lewis Carroll could be deeply amusing than generating amusement of comparable depth.

I honestly can’t tell if your remark about Williamson is itself a joke. Is it? Please state your answer in quantified modal logic.

I was not joking about Williamson. His jokes are unusually instructive and original. He gobsmacked one audience by simply lying to colleagues to generate an especially straightforward Gettier case—an actual one. Williamson does not work on delivery. Bill Lycan does—he has theatrical training. So does Alastair Norcross. So I read an Analysis article like “Consequentialism and the Unforeseeable Future” with Alastair’s voice in my head. Listening to him tunes up the voice and timing. Ditto, of course, for Lycan.

- The source of this report is Steven J. Bartlett (“Philosophy as Ideology,” Metaphilosophy 17.1 (1986): 1–16). I have no reason to distrust Bartlett’s report, but I tried to find a copy of the talk in Schilpp’s personal papers, which are deposited in the archives at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale. Although a copy of the talk doesn’t appear to have survived, I found an interesting essay that Schilpp published in 1975, “The Library of Living Philosophers: From a Personal Memoir,” about his work on The Library of Living Philosophers. (Schilpp’s article is a delight for the description on page 92 of Martin Heidegger’s scream but for other reasons besides.) Schilpp had retained an offprint of the 1975 article on which he added some marginalia and underlinings, presumably while preparing his notes for the later talk at Saint Louis University. In fact, one single handwritten page has survived, dating to the early ’80s. It could be a page from the talk Bartlett witnessed in St. Louis:

Thinking the whole lecture might have been published somewhere in some form, I picked up a copy of Schilpp’s memoir, Reminiscing: Autobiographical Notes (Paul Authur Schilpp with Madelon Golden Schilpp, Southern Illinois University Press, 1996). The memoir doesn’t mention any regrets about his career choices or his work on the LLP. In fact, near the end of the memoir’s narrative, he explicitly distances himself from regret about his life: “Sometimes I am asked if I had my life to live over again whether it would be the same. Actually, I think there is little I would change” (1996, 83). (I am grateful to Nick Guardiano for archival assistance and to Schilpp’s heirs, Margot and Eric Schilpp, for permission to reproduce the page from their father’s personal papers.)↑

Thinking the whole lecture might have been published somewhere in some form, I picked up a copy of Schilpp’s memoir, Reminiscing: Autobiographical Notes (Paul Authur Schilpp with Madelon Golden Schilpp, Southern Illinois University Press, 1996). The memoir doesn’t mention any regrets about his career choices or his work on the LLP. In fact, near the end of the memoir’s narrative, he explicitly distances himself from regret about his life: “Sometimes I am asked if I had my life to live over again whether it would be the same. Actually, I think there is little I would change” (1996, 83). (I am grateful to Nick Guardiano for archival assistance and to Schilpp’s heirs, Margot and Eric Schilpp, for permission to reproduce the page from their father’s personal papers.)↑ -

So you started with short discussion notes and then moved on to full-scale articles, like a weightlifter moves from small weights to heavier ones?

Yes. Once I could write a long one, I would have to write an abstract. The abstract often seemed to make the big article unnecessary. There is a temptation to show the reader the long way up the mountain you actually took. But once you reach the top, you can see shorter ways up. Readers correctly have zero interest in replaying meanderings and false paths. Referees often shorten the short cut.

Do you have any explanation for why philosophers these days don’t have more venues to publish short pieces, discussion notes, and squibs? Even Analysis, the classic 20th-century outlet for brief papers, now publishes long papers.

I have noticed that trend in Analysis. In grad school, I could publish a two-page squib in the Journal of Philosophical Logic, later a joke advertisement in Mind, and so on. Maybe standards of scholarship are rising? Gosh, I hope not!

By the way, I like your observation about showing readers the hard climb up the mountain rather than the short route. In her book The Writing Life, Annie Dillard notes there are “[s]everal delusions that weaken the writer’s resolve to throw away work.” We don’t throw out material when we should. Dillard asks: “How many books do we read from which the writer lacked courage to tie off the umbilical cord? How many gifts do we open from which the writer neglected to remove the price tag? Is it pertinent, is it courteous, for us to learn what it cost the writer personally?”

Could anyone compete with Annie Dillard’s gorgeous rhetorical questions? Could she go further and urge the author to make the reader feel like the one who got to the mountaintop first? Derek Parfit’s Reasons and Persons gave me this feeling. Parfit writes so simply that there is an illusion he is catching up to the reader instead of leading the reader.

-

Who did you have in mind?

Herbert Hendry. I remember him searching for an indigenous Scheffer function in an esoteric many-valued logic. His office blackboard had a matrix that became more populated with entries as he honed in on the function. One day I came to his office and saw that he had filled the matrix. He had finally discovered the function. “Where are you going to publish it?” I asked. He replied, “Not interesting enough” and erased the board.

Hendry’s Eraser wipes out good but insufficiently interesting work. Not every publishable thought must be published. But who decides what’s interesting enough?

I am enthusiastic censoring most of my thoughts. But Hendry’s small discovery was big enough for some form of preservation.

When you mentioned philosophers who don’t publish much, I thought immediately of Edmund Gettier. His celebrated 1963 article in Analysis is the only thing he published in his long career, but his colleagues and students report that when Gettier would sit down for a conversation over lunch or coffee, he would sometimes produce notes on napkins. How many publishable arguments did Gettier throw in the trash?

Gettier was a one-hit wonder. This is predicted by actuarial models of scholarly publication. As a graduate student, I read Gettier’s doctoral dissertation on the chance he was just a poor salesman of great ideas. The dissertation was fine but just one of very many fine dissertations. Therefore, I doubt his napkin notes were any better than the napkin notes of thousands of philosophers who were not as lucky as Gettier. Edmund Gettier was lucky that Bertrand Russell did not notice that his stopped clock example was a counterexample to ‘Knowledge is justified true belief.’ What makes Gettier significant is that he takes the standard methodology of an Analysis counter-exampler and blandly logic chops his way into a major discovery. Unlike his commentators, Gettier lacked the imagination to defend a definition that had passed the test of time. Gettier just puts his skunk into the epistemologists’ garden party. Instead of defending the skunk against its many perfumers, Gettier retires as a Sphinx.

- Letter XLV, “On Sophistical Argumentation,” paragraph 8.↑

-

There’s an ambiguity here. The word “labor” might mean working or childbirth. Which one is it?

The witty English professor wanted the ambiguity.

- Born Standing Up: A Comic’s Life (2007, New York: Simon & Schuster), 75. ↑

-

I’ll propose that music can be used to express a proposition—no lyrics required. Take Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony with the famous repeating idiom: three shorts and a long. In Morse code, that is “V” and the Allies during the Second World War used the idiom as a shorthand for “Victory”. And then J. S. Bach occasionally set his own name inside his music, a kind of musical cryptogram: B-flat, A, C, B (the German musical nomenclature calls B-flat “B” and B-natural “H”). Instrumental music seems up for the challenge of ‘arguing’ for a conclusion; it has rhythmic and tonal properties that can express information without words. I need to think of a musical argument, though.

One word is not a proposition.

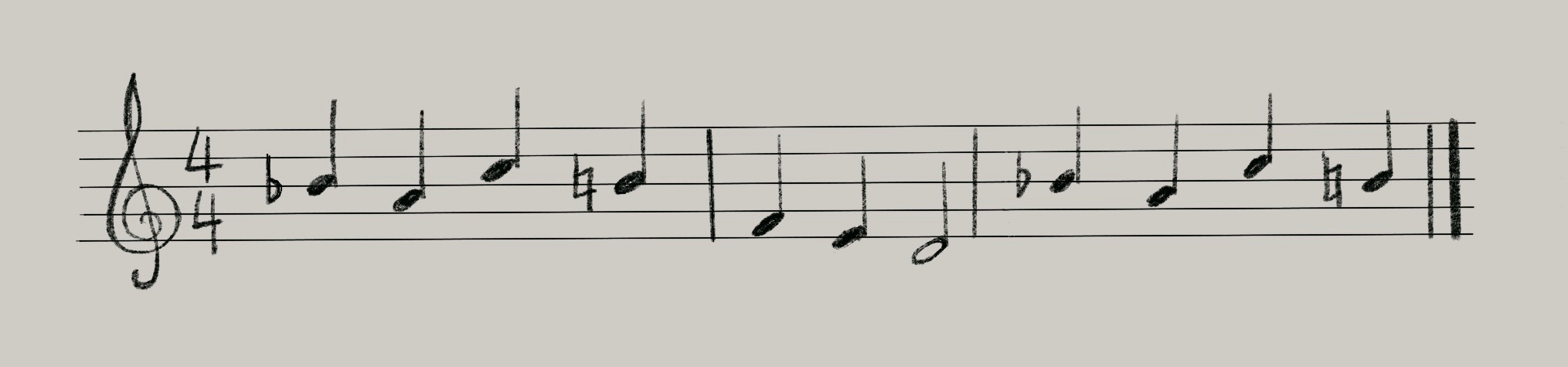

I wrote you a song:

That’s B-flat A C B F E D B-flat A C B. Bach fed Bach. There we have a declarative sentence at least.

Ingenious but since it is not my ingenuity, I am only envious, not persuaded. Your example seems like coding something discursive into a non-discursive medium, as when messages are written into photographs. But maybe I can horn in on your idea.

You might try leitmotifs. Perhaps the ominous music in the movie Jaws means the shark is near. Or maybe the leitmotif for Darth Vader in Star Wars expresses the proposition that the boy Anakin Skywalker is Darth Vader. When instrumental music is coupled to cinema, its status as “purely instrumental” is compromised. Cinema uses kaleidoscopic imagery to signal trippy intoxication. But kaleidoscopic images do not mean intoxication—or anything else!